COVID-19 news

COVID-19 situation reports from some of the APSR en bloc societies

December 2020

Hong Kong

President of the Hong Kong Thoracic Society

University Department of Medicine

Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong

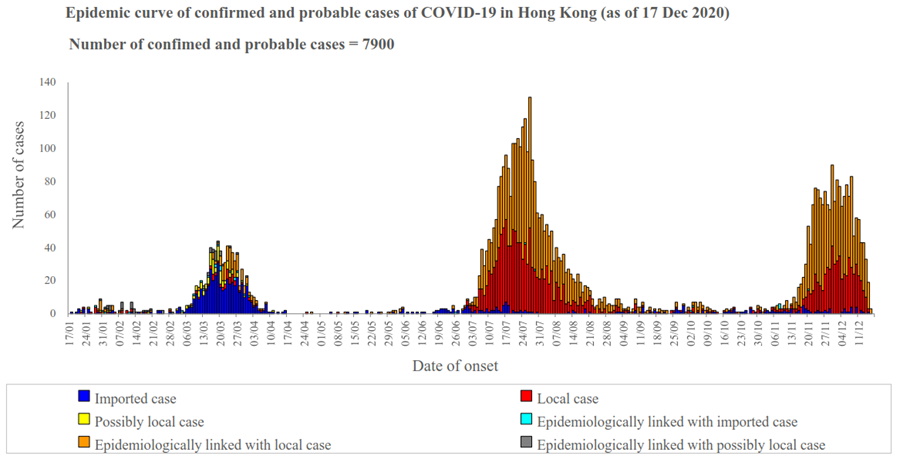

The first COVID-19 patient in Hong Kong was a visitor from China in January 2020. Since then, Hong Kong has experienced three waves of COVID-19 with mainly imported cases, with a surge in March 2020 when lots of Hong Kong youngsters returned from overseas, whereas in July 2020 another wave came with mainly air crews and ship crews arriving in Hong Kong. We have been experiencing the fourth wave since November 2020 with both imported cases and cases without clear origins (local cases). The cumulative number of confirmed cases has reached 7,900 with 125 deaths.

Hong Kong people have been practising universal masking, hand hygiene and social distancing. Most government offices, public facilities and schools were closed. Nonetheless, it is impossible to lock down the whole city and thus there are still imported cases from overseas. A compulsory quarantine period has been practiced for all people coming into Hong Kong.

There are always rooms for improvement. Measures like whole population testing and reinforcement of quarantine period have been suggested to enhance detection of infection.

Further graphics for Hong Kong from worldometers.info (PowerPoint file) submitted by Dr Philip Eng

Indonesia

Department of Pulmonology and Respiratory Medicine,

Faculty of Medicine Universitas Indonesia,

Persahabatan Hospital, Jakarta

Epidemic curve

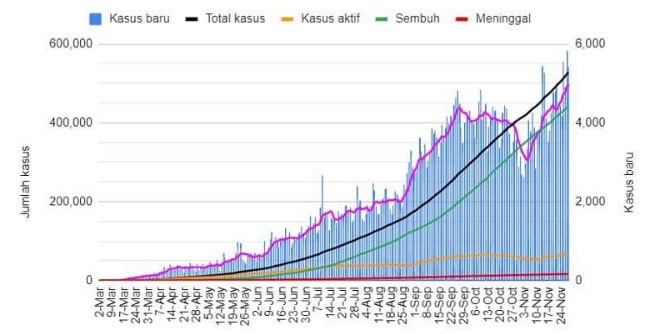

In February 2020, there were two related Covid-19 events in Indonesia, First, the Indonesian government evacuated 243 Indonesian nationals from Wuhan, China. Second, nine Indonesians on board the Diamond Princess tested positive for the virus and moved to treatment facilities in Japan. In both incidents they were placed under quarantine. On 2 March, the government announced the first two cases of Covid-19, and since then the number has increased to the current 617,820 confirmed cases, 18,819 confirmed deaths, and 5,000 – 6,000 active cases daily. Indonesia's cases are the highest number in Southeast Asia, ahead of the Philippines. In terms of the number of deaths, Indonesia ranks 3rd in Asia and 17th in the world. The number of deaths may be much higher that what has been reported since those who died with acute Covid-19 symptoms but had not been confirmed or tested are not included in the graphic below.

General comments about COVID-19

Indonesia has tested 4,308,544 people of its 269 million population; around 15,981 per million. The WHO has urged the nation to perform more tests, especially on suspected patients. Instead of implementing a nationwide lockdown, the government had approved large-scale social restrictions for some provinces and cities. This policy received much criticism and is considered as a disaster due to the still increasing number of cases. Even before the Covid-19 outbreak in Indonesia, capacity constraints in the health care sector have been an issue, like shortage of manpower and facilities, lack of protective equipment and operational funding issues.

Three things Indonesia has done well

Indonesia has made significant effort to provide Covid-19 tests for diagnosis. Nowadays, many health facilities can provide swab test or antigen rapid test. The government provides free Covid-19 tests in public health facilities and if people want to take paid test in private health facilities, the government has established the maximum price so that many people can take the test at an affordable price. Second, the government is already committed to providing free healthcare for anybody infected by Covid-19. Third, the government's commitment to provide Covid-19 vaccine.

Three things Indonesia could do better

The government could do better in three aspects which are:

- Raising people awareness and social response in implementing health protocol, strict rules and implementing a health protocol

- Better coordination and leadership amongst government leaders and all stake holders

- Increasing surge capacity in health facilities, testing, tracing and treating in all Indonesian provinces and protection for all health workers

Further graphics for Indonesia from worldometers.info (PowerPoint file) submitted by Dr Philip Eng

Japan

Akihito Yokoyama,

Japanese Respiratory Society (JRS)

Department of Respiratory and Allergology Medicine,

Kochi Medical School, Kochi University

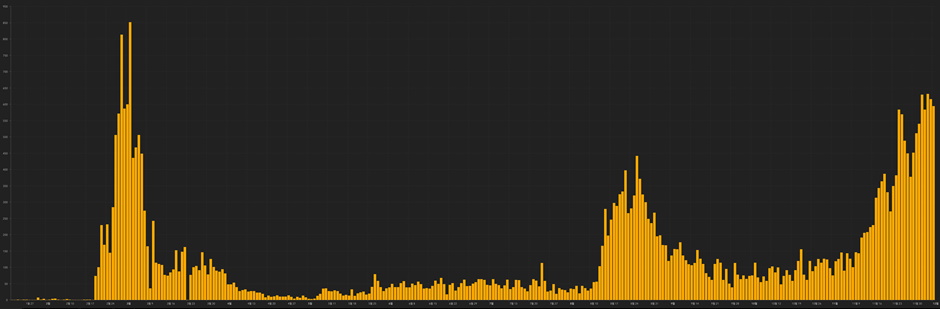

There have been three peaks of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic in Japan. The first occurred from mid-March to late May. The Japanese government declared a state of emergency on 16 April to avoid a collapse of the health-care system. This led to a decrease in the number of newly infected patients and stabilized the health-care system. Therefore, the state of emergency declaration was lifted on May 25. The second peak started in late July. Cluster infections of COVID-19 cases associated with restaurants and entertainment venues were reported, and infections became more widespread across Japan. Although more infections were reported during the second peak compared with the first, these cases were mainly young people, resulting in fewer severe cases and a lower fatality rate. After peaking in early August, the number of patients decreased and restrictions on social activities such as attending concerts and sporting events were gradually eased. However, in November, the number of infections began to rise again, along with the number of severe cases. As of early December, Japan is in the midst of a third peak.

Because of no or limited number of patients experienced in the 2002–2004 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and the 2009 swine flu pandemic, Japan did not adopt recommendations such as increasing the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing capacity and expanding the number of available medical staff. Although Japan entered the COVID-19 epidemic with these handicaps, it has endured without experiencing a collapse of the health-care system because of the sustained efforts of medical institutions, health centre surveillance, and public awareness.

The first thing Japan did well was slowing the spread of the disease during the initial peak without resorting to a strict lockdown. This was the result of the high awareness of infection prevention among the population and thorough infection prevention measures. In addition to general prophylaxis such as wearing face masks, handwashing, and gargling, the public also followed recommendations to avoid the “Three Cs” (closed spaces, crowded places, and close-contact settings). The second thing Japan did well was conducting retrospective epidemiological investigations and enacting countermeasures against cluster infections. Patients with COVID-19 and their close contacts were identified early and quarantined. In Japan, epidemiological surveys conducted to identify the source of infections for many infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis, have traditionally been conducted by Japanese health centres. The third thing Japan did well was keeping the mortality rate lower than that in the West.

The first thing the Japanese government could have done better was to have struck a better balance between restrictions and economic activities; however, the epidemic has not been adequately controlled and Japan is currently in the midst of the third peak of the epidemic. The second thing the Japanese government could have done better was to have been better prepared for an epidemic involving viral infections. As mentioned above, due to no or limited number of patients experienced in the 2003 SARS and the 2009 swine flu pandemic, recommendations such as increasing the PCR testing capacity and expanding the number of available medical staff were not adopted in Japan. In the early stage of the COVID-19 epidemic in Japan, the PCR testing capacity was poor compared with other countries, and not all patients who wanted a test could be tested. As the medical situation tightened, Japan experienced a shortage of skilled doctors, medical engineers and nurses who could provide extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and other advanced medical services. Even if the number of available beds can be increased, fostering skilled human resources takes time. The final thing the Japanese government could have done better was to have sped up the digital transformation of the health-care system, for example, through the development of online medical treatment and COVID-19 tracking systems. These remain future issues for Japan.

Graphics for Japan from worldometers.info (PowerPoint file) submitted by Dr Philip Eng

Korea

Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine,

Department of Internal Medicine,

Seoul St. Mary's Hospital, College of Medicine,

The Catholic University of Korea,

Seoul, Republic of Korea

In December 2019, the third novel coronavirus emerged in Wuhan, China. A previous study reported that severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was closely related to bat-derived SARS-like coronaviruses. The disease, which is now called COVID-19, is spreading aggressively worldwide. As of 8 December 2020, 67,653,117 cases and 1,545,824 deaths worldwide had been confirmed by the World Health Organization (WHO). On 20 January 2020, the first COVID-19 case in Korea was detected in a visitor from Wuhan, China. Since then, 39,432 cases have been confirmed and 556 deaths reported by the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) as of 8 December 2020. (Figures 1 and 2)1. This paper aims to evaluate what Republic of Korea did well and what the country could do better in its response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Three things Republic of Korea did well

Readiness for emerging infectious diseases

An outbreak of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) occurred in Republic of Korea from May 2015 to December 2015. The MERS coronavirus infected a total of 186 people, 38 of whom have died, and that was the largest outbreak outside the Middle East2. With the lesson learned from the MERS outbreak, the government and hospitals have been preparing for the inevitable outbreak of emerging infectious diseases. The Korean government has supported $32.5 million to treat infectious diseases, designated 165 general hospitals and 20 tertiary hospitals as specialized regional infectious disease hospitals, and furnished them with isolation rooms and system setups3, 4.

Expansion of diagnostic tests and low-contact testing centres

Early detection and assessment of potential cases are critical to reducing the transmission rate of COVID-19. Republic of Korea focused on rapid and widespread testing, rather than locking down the entire city. With the expedited approval system for the urgent test kit use, a single-step, real-time RT-PCR test kit for SARS-CoV-2 that takes 6 hours was approved and available as early as 31 January this year5, 6. In December, more than 1,050 private and public health care facilities could perform diagnostic tests. The government covered the cost of tests meeting case criteria7.

In February, the first drive-through testing centres opened in Goyang, Gyeonggi province, at the city hall parking lot. The testing process, including registration, symptom check, swab sampling, and car disinfection, could be completed in less than 10 minutes for each potential case8. A walk-through diagnostic booth was created for pedestrians and used to maintain negative pressure within the testing area. Early detection of potential cases and the isolation of confirmed cases were effective in preventing COVID-19 transmission.

Response to the regional outbreak

The city of Daegu, Republic of Korea, had the first large outbreak of COVID-19 outside of China in February. As the COVID-19 spread rapidly in Daegu, a shortage of hospital beds, supplies, and health care workers occurred. There were 51 of the 54 available negative-pressure isolation beds within the city occupied only four days after the first confirmed case of COVID-19. By the end of March, more than 2,000 patients were waiting for hospital beds9. Health system leaders and public health officials rapidly adopted a regional risk stratification and triage system and recruited health care workers from other regions. In response to the shortage of hospital beds, health officials in Daegu created more than 400 negative-pressure rooms across the city. The city designated 10 hospitals only for COVID-19 patients and identified available beds in other nearby cities where they could transfer patients from Daegu who required hospital-level care9. Despite the enormous pressure on the health care system, Daegu successfully overcame the COVID-19 outbreak.

Three things Republic of Korea could do better

Rapid response to changing epidemic pattern

Despite the aforementioned efforts, Republic of Korea has been experiencing its third COVID-19 wave since the end of November in the metropolitan area (Seoul and Gyeonggi province). The nation is experiencing multiple infection cases in which the source cannot be specified, unlike in previous patterns. In the past, each time the epidemic surged in a particular region, the government tried to track and isolate as many cases as possible, and the number of transmissions fell within a couple of weeks. But this surge could be different. The winter season has arrived, and the cold and dry air conditions could be potentiating factors on the spread of SARS-CoV-210. Furthermore, as indoor activities increase due to the cold weather, the spread of SARS-CoV-2 is likely to become easier. At the beginning of the third COVID-19 wave, the level of social distancing should have been raised to prevent the COVID-19 epidemic. However, the government reacted slowly. As a result, COVID-19 infection has not decreased since the end of November.

Intensive care unit preparation for COVID-19 patients

With the rapid increase of COVID-19 patients from the end of November, the number of critical patients who require intensive care unit (ICU) admission is also increasing. Since 10 December, an average of 600 COVID-19 cases have been confirmed each day. Despite the soaring number of patients, the government reported that only eight ICU beds remained unoccupied that week in the entire metropolitan area11. After the second wave of COVID-19, healthcare officials should have better prepared for the expected surge in winter. However, rather than securing ICU beds or organizing a systemic intensive care system to reduce the number of COVID-19 patients, the government seemed to be more focused on recovering the business sector. The government should implement policies such as designating hospitals for critical COVID-19 patients or securing ICU beds in large tertiary hospitals before the healthcare system collapses.

Comprehensive and consistent anti-epidemic measures

Republic of Korea is a small, overpopulated country (51,289,308 inhabitants in 100,363 km2). Due to the development of transportation, the whole country became a half-day living area. Although millions of people move between cities every day in the metropolitan area, adjacent cities and provinces undertook different anti-epidemic policies. Inconsistent social distancing levels between other regions may bring a ‘balloon effect', since the current third wave in Republic of Korea is not happening in a specific cluster but through community transmission. Therefore, it is necessary to establish a comprehensive and consistent anti-epidemic policy, especially in the metropolitan area.

Recently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued the first emergency use authorization for a Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine for the prevention of SARS-CoV-2 infection12. Other COVID-19 vaccines will soon be developed and someday be available in Republic of Korea. However, at least one more surge of COVID-19 could happen before the vaccine is sufficiently distributed. After overcoming this third wave, we need to be thoroughly prepared to cope with another wave rather than being satisfied with the result.

Further graphics for Korea from worldometers.info (PowerPoint file) submitted by Dr Philip Eng

Malaysia

Pulmonology unit, Department of Medicine,

National University of Malaysia (UKM) Medical Centre,

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Introduction

On the 31 December 2019, pneumonia of unknown cause emerged in Wuhan city, Hubei Province of China. These cases were confirmed by the World Health Organization (WHO) on the 5 January 2020. The ministry of health (MOH) of Malaysia gave a prompt first press release for the 2019 Novel Coronavirus on the 6 January 2020. On 11 February 2020, WHO declared “COVID-19” as the official name for this disease.1 Thereafter, a global lockdown ensued due to the exponential increase in the transmission of COVID-19.

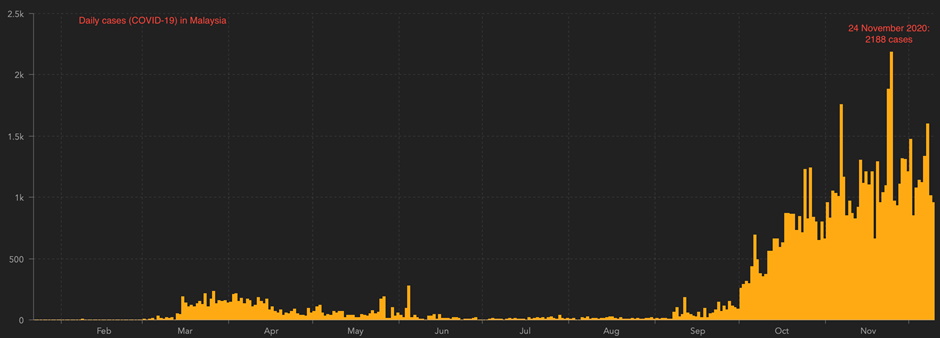

COVID-19 in Malaysia

Overall, the pandemic has resulted in three waves of outbreak in Malaysia. The first outbreak was from travellers from China arriving through Singapore on the 25 January 2020. The nation witnessed its second wave after an international religious gathering held in the capital city of Kuala Lumpur from 27 February until early March 2020. Malaysia learned from the tragic lesson in Italy and implemented a movement control order (MCO)-partial lockdown, effective from 18 March 2020 until 9 June 2020 to help to contain the outbreak. Strict enforcement was conducted during the MCO period. Only essential services were allowed to operate under stringent operating protocols. The result of the MCO has “flattened the curve” of COVID-19 in Malaysia. The initial R-nought (R0) of 3.5 was reduced to 0.3.2 With the transition to a conditional MCO and subsequently recovery MCO, some restrictions were lifted in phases with the resumption of economic activities. However, the conditional MCO was re-implemented to some high prevalence regions during the third wave of outbreak in October. As of 10 December 2020, Malaysia recorded a cumulative 76,265 cases with 393 deaths.

The unprecedented outbreak in Wuhan, China, has resulted in high mortalities. This was due to the sudden surge in the number of cases that had overwhelmed its healthcare system. Thus, the MOH initiated planning and preparedness activities that focused on "surge capacity" as early as January 2020. The MOH ensured designated tertiary referral centres were set up in all states. These referral centres' bed capacity increased mainly by converting less utilized spaces and buildings into medical wards. Nationwide, a total of 60 temporary quarantine and low-risk treatment complexes were set up to house non high-risk cases. Data from both China and Italy have demonstrated that approximately 10% of patients with COVID-19 require intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and mortality rates for these patients can reach up to 50%.3 Thus, increasing the capacity of ICU beds and ventilators were heavily emphasized. All elective hospital admissions and procedures were postponed. Some health services were migrated to the telehealth platform to ensure the continuation of care for the patients. The existing smaller hospitals and the community health centres that served as screening centres were supported by the rapid response and assessment teams that facilitate risk assessment, testing, contact tracing, and various logistics of the outbreak.

Meanwhile, the MOH also developed rapid interim protocols for screening and testing from the pandemic's start. All nationwide laboratories were provided first-hand training as early as 13 January 2020 to ensure these laboratories' diagnostic capacities were optimized. By the end of September 2020, when Malaysia experienced the third wave, the nationwide laboratory test capacity exceeded expectations. To avoid smaller laboratories from being overwhelmed, especially in states that faced significant outbreaks, the MOH embarked on a collaboration with the Royal Malaysian Air Force and the national courier to urgently transport samples for testing at the Institute for Medical Research in Kuala Lumpur. Other remedial steps also included outsourcing testing services to private laboratories. Despite the global shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE), the MOH, with the support from various non-governmental or charity organizations, has taken adequate measures to ensure the proper supply of PPE for health care workers (HCWs).

During the pandemic, the MOH acknowledged the importance of the availability of human resources. To avoid this shortage, the MOH has made numerous efforts to recruit retired HCWs and volunteers, and some HCWs were temporarily redeployed to areas of significant outbreaks. The psychosocial well-being of HCWs was provided with top priorities. Many HCWs inevitably developed exhaustion both physically and psychologically. The Malaysian Ministry of Health initiated mental health and psychosocial support services (MHPSS). It is integrated with various non-government organizations and volunteer bodies to assist distressed HCWs.

The MOH drafted treatment protocols and released guidelines periodically tailored according to the latest available evidence. Asymptomatic patients were quarantined for monitoring. High-risk individuals were closely monitored in hospitals. Among medications explored included hydroxychloroquine (most frequently used) followed by various antiviral therapy. Lopinavir/ritonavir was used in 77% of severe cases.4 Steroids were initiated in slightly less than a quarter of severe COVID-19 patients before the Recovery trial published results. Patients with respiratory failure were provided with necessary ventilatory support. Some centres sparingly explored awake prone ventilation. Critical care units had a low threshold for intubation for patients with severe respiratory failure due to dilemmas faced, such as aerosol generation and patient self-inflicted lung injury (P-SILI) with the use of non-invasive ventilation therapy. Another reason was that early intubation could enhance the safety and protection of HCWs compare to emergency intubation. On the research front, Malaysia has also participated in the global Solidarity trial launched by WHO to help find an effective treatment for COVID-19.

Excellence in handling the pandemic

Throughout the pandemic, the safety and well-being of all HCWs remained MOH's top priority. The available resources were never compromised. HCWs comprised approximately 4% of the total number of confirmed cases recorded nationwide. As of 9 September 2020, there were no HCW infected while managing confirmed cases. More than half of the total cases reported (53%) occurred due to workplace transmission among HCWs. Work-related transmission mainly occurred from the inadequate use of PPE while managing non-suspected cases.5

The MOH held daily press conferences throughout the pandemic. The public has easy access to these updates through the media and various social media platforms. Daily updates included the number of active cases, mortality rates, distribution of cases, bed occupancy and ventilator usage, and PPE sufficiency. Health advisories and updates were also delivered to all cellphone users via short message services to increase awareness among the public. A standardized electronic application was also introduced for the people. This "all in one" application incorporated multiple features such as updates on COVID-19, location check-ins, tracking services, information, and resources on COVID-19.

Malaysia has a massive 2-3 million migrant worker population and 178,540 refugees and asylum seekers reported by the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) in October 2020. The MOH also ensured that the welfare of these migrant workers, refugees and asylum seekers were not overlooked. Cooperation between MOH, UNHCR and other NGOs helped provide testing and treatment without additional cost.

Addressing the shortfalls during the pandemic

A third wave let down Malaysia's success in controlling the outbreak at the end of September 2020. This was contributed by the public's complacency over government advisories once previous restrictions have been lifted. The MOH should collaborate with all stakeholders to draw up new measures and protocols to tie up loose ends in tackling the pandemic.

There were also clusters of infection attributed to withholding history by close contacts of disease or individuals who had returned from recent outbreak areas. For this reason, the ease of certain restrictions in particular to screening at entry points and social gatherings could be done at a much gradual pace. Contact screening could also be extended beyond close contacts of infection since the capacity of testing has increased at all laboratories.

Throughout the pandemic, recurrent clusters of infection have been reported involving migrant workers. The MOH could reach out to this group by conducting a regular awareness campaign at the workplace. More efforts are needed to address overcrowding and the lack of awareness of the pandemic among migrant workers.

Conclusion

Malaysia has witnessed many challenges during the global pandemic of COVID-19. The government has taken bold and prudent decisions to control the pandemic, and all these efforts have exceeded expectations. The sustainability of these efforts is crucial to continue to safeguard the general public's well-being.

Further graphics for Malaysia from worldometers.info (PowerPoint file) submitted by Dr Philip Eng

Mongolia

President of the Mongolian Respiratory Society

Overview

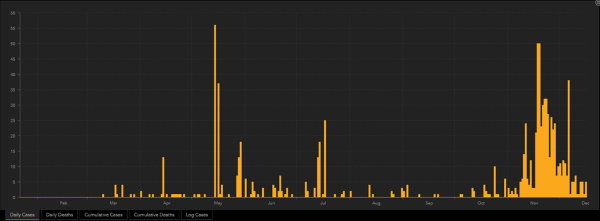

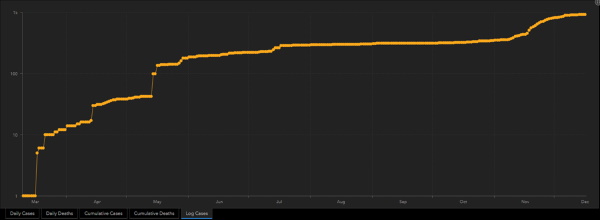

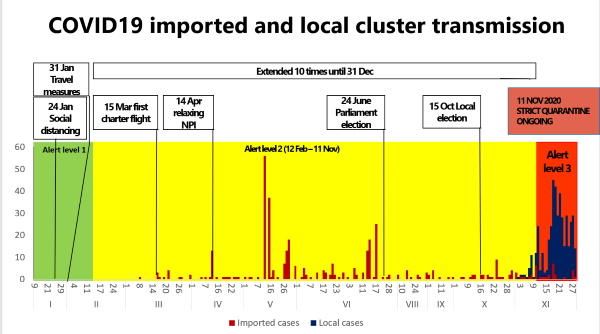

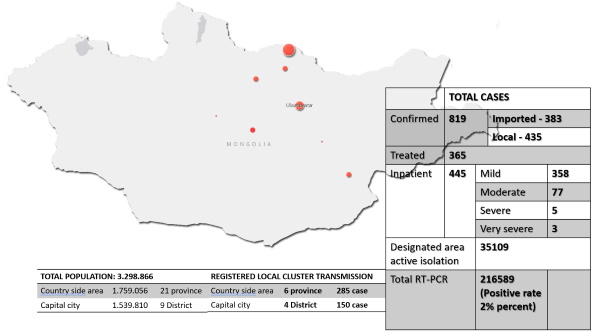

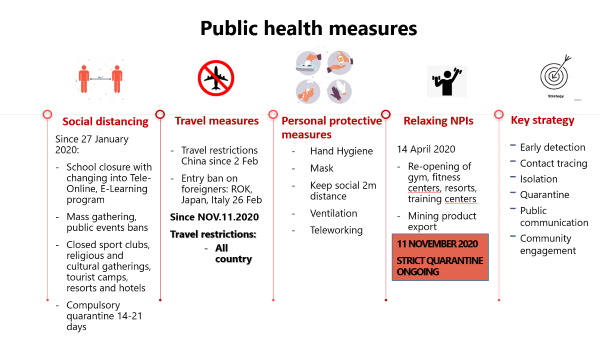

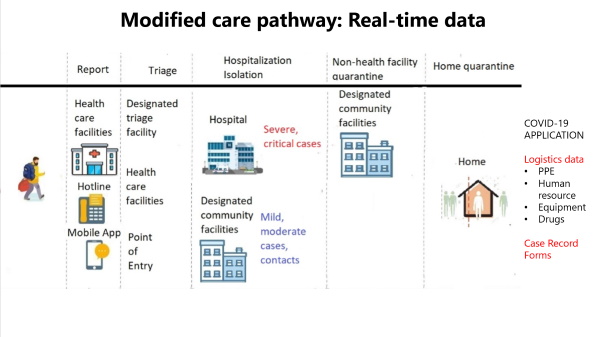

Although Mongolia controlled the spread of COVID-19 with no domestic infection by having strict border controls, the first domestic cluster of the new infection was registered on 11 November 2020 by an international land transport driver. Currently there are ten cluster outbreaks in Mongolia, of which one cluster has not been fully identified and surveillance is underway.

It is almost impossible to have home self-isolation due to the traditional lifestyle of Mongolians, as about 55 percent of Mongolia's population live in traditional Ger districts. For them, the risk appears to be more costly than hospitalization. But it is possible for most small families living in a house or apartment with separate rooms for family members.

More than 80 percent of those currently confirmed COVID-19 patients being treated are asymptomatic and mild due to high screening coverage. They are prevented from the spreading infection to close-contacts, as well as being provided with early treatment and having reduced complications.

The total number of confirmed cases of coronavirus is 953. There are 435 cases currently being treated and observed in home isolation. Fortunately, there are currently no deaths from COVID-19 in Mongolia.

Three things Mongolia did well

- State border closure except common needs

- Short term "strict quarantine" – tracing and control the spread of infection

- Mass PCR screening in cluster transmission areas for household members of each family

Three things Mongolia could do better

- Increase capacity of health care facilities and equipment used to treat COVID-19 patients

- Ensure access to socially vulnerable people's services

- COVID-19 inclusion of financial needs for regulatory services in social insurance

Further graphics for Mongolia from worldometers.info (PowerPoint file) submitted by Dr Philip Eng

Philippines

Board Member, Philippine College of Chest Physicians

Date Submitted: 20 December 2020

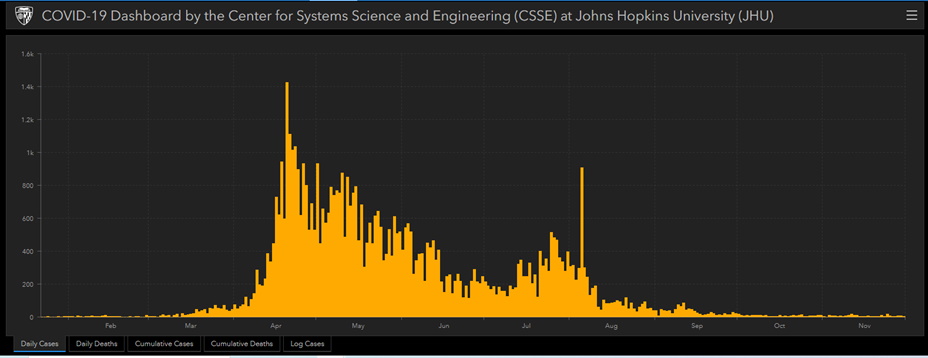

General trends

On 20 December, the total number of cumulative cases in the country was 458,044 with a total cumulative number of recoveries at 421,086 and total deaths at 8,911. Currently, there are just over 28,000 active cases in the country. Of these active cases, 83.4&percentare mild cases, 8.8&percentare asymptomatic, 4.9&percentare critical, 2.5&percentare severe and 0.30&percentare moderate.

Looking at trends in terms of active cases, there seems to be some spikes in new cases reported which started on 16 December after the encouraging numbers of less than 1,500 cases during the first two weeks of December. Certainly, these figures are better compared to the situation in August where the highest number of new daily cases was reported at more than 6,000.

The death figures were characterized by "ups-and-downs". Daily numbers tend to hover around 40-80 with the worst figure being over 200 last mid-September. A spike of over forty was reported around 15 December followed by a relative decline. A steadier down trend seems elusive.

General comments and observations

The general trends in terms of new cases seem to reflect the periods when there were some efforts in terms of opening-up the economy in the country. During such times, there was a lot of movement especially in the labour sector and quarantine measures became less tight. Even though there was a consistent public health message regarding minimum safety protocols since the start of the pandemic, its strict observance was, unfortunately, not uniformly seen. In addition, mechanisms for their implementation were delegated to local government units. As such, in some specific areas, these measures were strictly enforced whereas in others, these were sadly below the standard. Relative surges in numbers this December coincided with the observance of dawn masses that is a Filipino tradition to usher in the season of advent.

This balance was extremely delicate. In a lot of instances, "localized lockdowns" or a "granular approach" was adopted and was deemed a proportionate response based on the local needs. This offered some success as decisions and policies relied on data and its subsequent adaptations.

Testing was also a challenging item. The country was really plagued by matters related to this. Its availability, its access, its target in terms of priority, its cost, and its regularity. This has been a huge hurdle to overcome especially at the start. The University of the Philippines-Manila National Health Institutes (UP-NIH) created its local testing laboratory and testing kits during the initial stages of the response and this somehow added to the efforts of unburdening the diagnostic system which was already stretched. The national figures were also affected in terms of timely reporting coming from these testing centers. The delays somehow created some confusion at the start since figures were deemed not to be compatible with what was being felt and observed at the frontlines.

The government's Inter Agency Task Force on COVID-19 (IATF) became the main body in terms of orchestrating the country's general framework against this pandemic. The IATF is made up of relevant cabinet secretaries, scientists and medical professionals, and policy makers. This body is quite dynamic and active with recommendations that are crafted after every 2-4 weeks of situational analyses and assessments. These are subsequently announced by our president at regular intervals. This body is also quite sensitive to the situations at the frontlines especially from feedback mainly emanating from professional medical societies.

The government also designated 75 COVID referral hospitals all over the country as of last April. It targeted to have at least one COVID-19 facility per region. Being a COVID referral hospital (CRH) has certain privileges which may be availed of during this government's pandemic response. These include procurement of needed equipment and medications (even outside the Philippine Drug Formulary or PDF), manpower strengthening by being prioritized for volunteer augmentation, and a more streamlined fast-tracked procurement process. In addition, management interventions, even those which are deemed as experimental, will also be more available. This set-up was envisioned to be able to equip these facilities better as afflicted individuals will be directed to these sites. This mechanism was generally regarded as a positive step in this overall response framework.

A very dynamic group of local medical societies have collaborated so that medical recommendations can be updated and a critical appraisal of literature can be made available in a timely manner. In addition, these statements were tried to be more locally relevant by pointing out particular realities on-the-ground that may influence implementation. These "rapid reviews" equip the physicians to weigh potential options and appraise their patients accordingly. These have also influenced policies and public health messages.

A One Hospital Command Center (OHCC) was also created by the Department of Health (DOH). This body, headed by an undersecretary by the DOH, was the main coordinator among all hospitals so that policies and information pertaining to bed and ICU capacities and patient transfers could be easily disseminated and all facility directors could expedite implementation. It was hoped that with this set-up, all hospitals would be moving in "one direction" with patients (both COVID and non-COVID) being absorbed by the appropriate center considering its available bed and services. A daily morning meeting was conducted among hospital directors for regular updates and possible suggestions to improve the existing system.

Throughout this pandemic, the generosity or what we term as "bayanihan spirit" by the Filipinos surfaced and was palpable. Contributions from the private sector, non-government agencies, the academe, and other member of society greatly augmented the supply from the government. These materials ranged from PPE's, scrub suits, medical supplies and equipment like ventilators and high flow nasal cannulas, transportation services, regular food supply, and even accommodation facilities. The initial months of the pandemic really brought uncertainty and anxiety among frontliners. Certainly, when things began to settle down and coordination of efforts became apparent, fear was slowly replaced with hope and a certain amount of optimism.

The last three months ushered in some degree of acceptance in terms of what the "new normal" will look and feel like, more consistent messages to the public from the policy makers and scientific community, stern warnings to comply with health measures being implemented, and a calmer response to increases in numbers in some cities and regions. Although there were still some uncertainties with this pandemic, government reactions were quite proportionate and due consultations with the relevant parties were made. At this stage, cautious optimism seems to be the pervading attitude as we await the arrival of vaccines in the country. This will definitely be accompanied by its unique set of challenges at this chapter of the country's COVID-19 response.

Three things the country did well

- Creation of specialized bodies

Examples include the OHCC and the IATF. Specific powers and tasks govern these entities. Such action orchestrated a lot of effort and paved the way for timely delivery of services and minimized miscommunication and confusion on-the-ground. - Appreciating and acknowledging efforts from other sectors

Volunteer groups were welcomed by the government and their efforts were coordinated, encouraged, and publicly appreciated. The government was quite transparent with its limitations and openly reached out to field experts and potential donors. This also included advice from the medical communities that assisted in recalibrating responses and data-driven policies.. - "Bayanihan Acts" (laws to facilitate fund release)

Special laws were crafted at the initial stage of the pandemic. These paved the way for unquestionable fund release to augment needed resources including staffing and manpower concerns of CRH's. Procurement of necessary equipment especially for critical services was likewise addressed.

Three things the country could do better

- Crafting of clear and concise public messages and their implementation

Messages could have been more frequent, science-based but comprehensible by the lay public. Such a mechanism could allay fears and ensured better cooperation from the masses and ensured their consistent compliance to public health standards. Opening up of the economy could be done in a transparent, slow but sure manner.. - Availability and access to rapid diagnostic test kits and centres

Calibrated responses could have been bolstered if this mechanism was available early on. In addition, decisions were heavily dependent on these especially during periods of surges and when frontline management could be facilitated if the COVID status of critically ill individuals was known. Turn-around times and timely reporting to national figures are also significant intertwining issues.. - Ensuring non-covid services are not left behind in the pandemic response

These services remain crucial as CRH's also address essential non-covid services in their specific localities. OHCC could have assisted coordination among hospitals so that "no one will be left behind" and no service will suffer or cease amidst this pandemic response.

Graphics for Philippines from Johns Hopkins (PDF file) submitted by Dr Jubert Benedicto

Further graphics from worldometers.info (PowerPoint file) submitted by Dr Philip Eng

Singapore

Affiliation; Mount Elizabeth Hospital

En bloc society; Singapore Thoracic Society

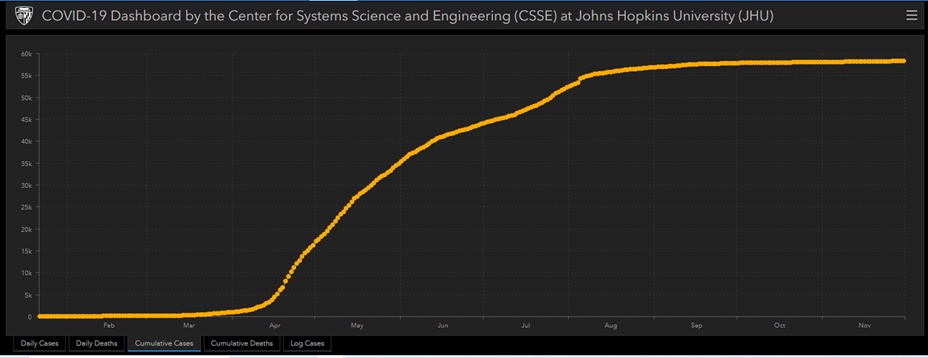

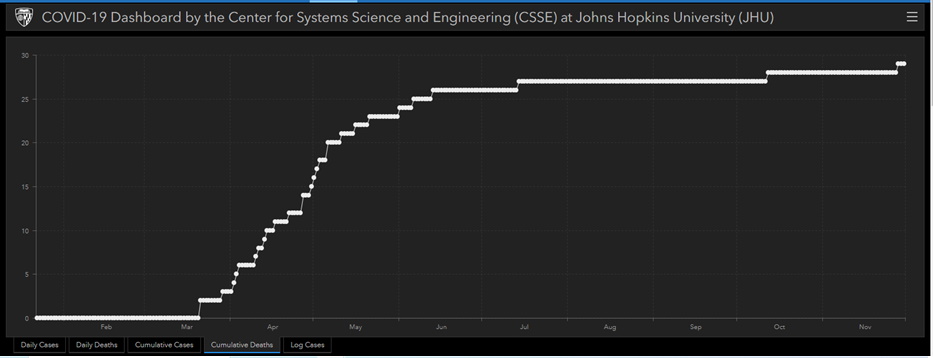

Like most countries, Singapore has had to deal decisively with the COVID-19 pandemic. As of 1 December 2020, Singapore's recorded 58,228 cases of COVID-19 (9,920 per 1 million population), whilst deaths from COVID-19 numbered at 29 (5 per 1 million population). There were 4,658,858 tests performed (793,690 tests per 1 million population)

What has Singapore done well in handling the local COVID-19 situation?

- Our government has been pro-active in implementing numerous control measures including strict travel bans, temperature screening at public places, contact tracing, compulsory mask-wearing, and social distancing policies. Hand sanitisers had also been freely distributed to the local population, while free masks are available via self-service vending machines. Local community cases have generally been in the single digits over the past few months.

- Drawing on experience from SARS previously, our medical facilities were able to cope with the surge of COVID-19 cases, as well as coordinate large scale COVID-19 swab/serological testing efforts. Quarantine facilities were rapidly converted and utilisation of event/sports halls (and a cruise ship) provided isolation of positive/suspect cases.

- Our advanced research facilities have also allowed local scientists to collaborate, develop COVID rapid PCR tests, and also develop a COVID vaccine candidate.

What could Singapore do better about the COVID-19 situation?

- As the country gradually relaxes various measures, there have been reports of large groups gathering illegally and flouting safe distancing measures. Enforcement efforts must be maintained to ensure Singapore avoids an escalation of COVID-19 spread.

- Dealing with COVID-19 transmission in the foreign worker dormitories has been challenging due to crowded living conditions amongst these workers. The Singapore government is looking to improve dormitory designs to mitigate future risk of spread.

- While it is mandatory to check in to various institutions/public areas like shopping malls, schools, hospitals, contact tracing could be further improved as our local contact tracing automated TraceTogether programme, consisting of a Bluetooth enabled app and token, has not received the desired uptake yet. More publicity material and public education may improve the uptake.

Further graphics for Singapore from worldometers.info (PowerPoint file) submitted by Dr Philip Eng

Sri Lanka

Dr Chandimani Udugodage - Faculty of Medicine University of Sri Jayewardenepura

Dr Neranjan Dissanauake - General Hospital Rathnapura

Dr Aflah Sadikeen - National Hospital Colombo

Dr Nandika Harischandra - Teaching Hospital Anuradhapura.

Dr Bodhika Samarasekara - District General Hospital Gampaha

Where we were and where we are

COVID-19 is by far the biggest health challenge the world has faced in since the Spanish flu way back in 1918. As Sri Lanka watched COVID-19 unfold, there was wishful thinking on our part, with the warm weather and the eternal sunshine, and we would be spared of the wrath of COVID-19. The first case in Sri Lanka was detected on 27 February in a patient of Chinese nationality. Still we held on to our unwavering faith and optimism.

The first Sri Lankan patient was diagnosed on 11 March and two more cases were soon to follow. In view of the uncertain eventuality the government proactively closed the schools and the closure of the airports were soon to follow. Within a week, the country was in a state of lockdown with island wide curfew. At the same time the ministry of health issued a Clinical Practice Guideline on COVID-19, which introduced the concept of a COVID-19 triage area and a COVID-19 suspect ward while addressing case detection, disposition of patients, lab diagnosis, infection prevention control, management of high risk patients, and maintaining welfare of the HCWs. As time progressed, the case detection was mainly from overseas returnees. The lockdown was lifted and the country gradually returned to a "new normal". Subsequently two large clusters which emerged from a Naval base and a drug rehabilitation center were successfully contained.

As it was widely believed that there was no community transmission and the public lulled into a false sense of security. The schools re-opened. The general election was held. The public moved from the "new" normal back to the "old "normal and the travelling and socializing resumed.

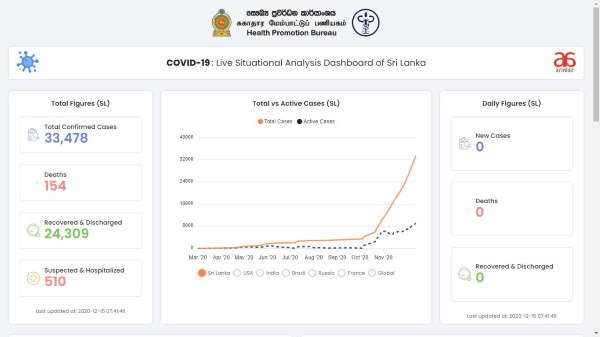

On 4 October a COVID-19 patient from a garment factory was detected as a result of the surveillance mechanism set up by a respiratory physician. The contact tracing from this led to the garment factory and fish market clusters and the number of cases rose exponentially to a staggering 33,478. The death rate increased with 154 deaths at the time of writing. The draconian social restrictions were reinstated which included closure of schools, universities and the lockdown of high risk areas. Although the situation is somewhat controlled, the daily cases are still on the rise. This is where we are at present.

What we did right

During the early stage of the pandemic, the Sri Lankan government established a National Task Force for COVID-19, comprising all major stakeholders. The task force coordinated with the defence authorities including the state intelligence services for contact tracing and mobilization of resources. More than 50 quarantine centres were established to accommodate large numbers of inbound arrivals of repatriated Sri Lankans. These were designed and successfully managed by the defence personnel. This provided the much needed assistance to the health care system to accommodate the rising numbers. The mandatory quarantine period of 14 days was strictly adhered to, to prevent the disease reaching the community.

All the positive PCR cases, regardless of the symptoms, were admitted to state sector establishments. This further prevented the disease spread in the country. The operational cell, COVID-19 triage areas and isolation units were established in each hospital and new treatment centres identified by utilizing the available local resources to accommodate those with symptoms.

What we did wrong

Although these measures ranked Sri Lanka amongst the top countries to have successfully controlled COVID-19, there were shortcomings which probably led to the current predicament. The two-phase strategy of the "hammer and dance" which Sri Lanka adopted could have been better managed. An effective and a robust screening programme targeting the high risk population during the period of dance /"new normal" following the lockdown would have prevented the emergence of clusters. Although COVID-19 PCR was done continuously, the number of tests per day was insufficient and the screening populations were not correctly identified. There was clearly a lapse in vigilance. The golden hour that was presented to us during the period of "hammer"/lock down when the number cases were low, was not used to its maximum. This period could have been more effectively utilized to strengthen the infrastructure, equipment, manpower, expertise, training, and establishing systems in hospitals, in order to be better prepared to face the challenge once the numbers rise. Although the media played a significant role in creating public awareness about the disease and its preventive measures, it also had a negative impact on the public by stigmatizing patients and their families. This led to a reduction in health-care seeking behaviour of patients, thereby leading to reduced case detection and increased number of deaths occurring at home. The better governance of the media for a positive impact on psychological and spiritual wellbeing of people would minimize the above shortcoming. COVID-19 has brought the mighty mankind down to its knees. The lessons learnt from this pandemic will see us through, in the years to come. Vigilance, perseverance and unity is the way to victory.

Further graphics for Sri Lanka from worldometers.info (PowerPoint file) submitted by Dr Philip Eng

Australia and New Zealand

Jacky Dawkins1 and Bruce Thompson2, 3

2 Faculty of Health, Arts and Design, Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn, VIC, Australia.

3 President, Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

This year has been one steep learning curve for all Australians as the impacts of COVID-19 have been felt immensely across the globe. As the year comes to a close, it is important to reflect upon the resilience and hard work of all individuals, both in Australia and internationally. To those who have been working either directly on the front line or behind the scenes, we cannot begin to articulate how grateful we are for your hard work and dedication during this difficult time.

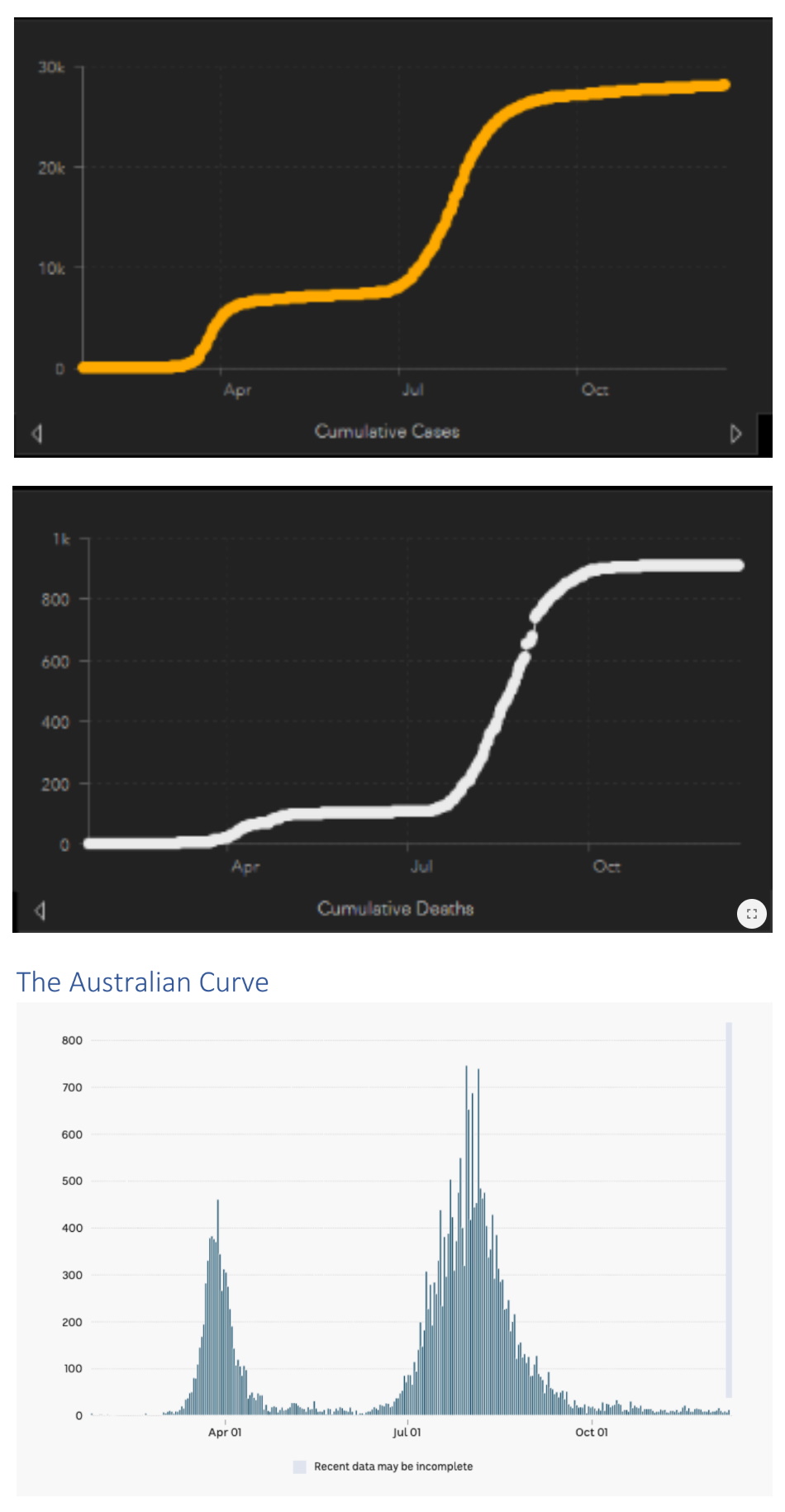

At the present time, Australia has an estimated 137 active cases, with no new recent deaths.

As at late-December, there has been a recent outbreak in the Sydney metropolitan area that has now led to border closures between all States and New South Wales and a further tightening of restrictions in the greater Sydney area, with other States' borders remaining open for travellers arriving from the remaining States and Territories. Due to the unpredictable nature of the virus, Australia has upheld certain restrictions such as social distancing in public areas, as well as restrictions for public gatherings and limited capacity at all commercial venues. These measures are still in place to assist with any outbreaks in the community and to help contain the virus in the event of an unexpected outbreak.

During the initial outbreak in March, the Australian Federal Government decided to lock down our international borders, along with State Governments implementing restrictions to slow the spread of the virus. The measures implemented included (but were not limited to) mandatory quarantine for all returning travellers, the establishment of contract tracing and widespread testing services, as well as the closure of all retail stores, restaurants, sporting events, and public gatherings. This lockdown was implemented fast, early, and hard, which added to its overall effectiveness.

The negative economic effects of the pandemic and lockdowns are also being felt by many Australians. We are now in a national recession, with the national unemployment rate currently sitting at 6.8%i. There is still a long way to go before we make it through to the other side, and yet there are considerable consequences, both socially and economically, that will be felt for many years to come.

The Positives

Australia has so far been relatively successful in managing the pandemic thanks to our national and State lockdowns. The rapidity of our national border lockdown prevented many international cases from affecting the general population, with States introducing lockdowns for subsequent localised outbreaks.

Each State has had a varied experience in terms of managing the pandemic, in particular the State of Victoria when they experienced a strong second wave that led to a strict Stage 4 lockdown. During this period, residents were limited to a 5 km geofence around their primary residence and an 8 pm curfew was implemented. Within this geofence, Victorians were only permitted to leave their home for their grocery shopping, medical appointments, the pharmacy, and 1 hour of exercise per day. The effectiveness of this lockdown is demonstrated through the numbers alone – currently, Victoria is sitting at 52 days since the last locally acquired case and there have been no recent deathsii. Other States and Territories have had varied experiences with the virus, with Western Australia, Northern Territory, South Australia, Australian Capital Territory, Queensland and Tasmania all maintaining low infection rates, whilst NSW is now facing a large cluster outbreak.

Another positive approach of Australia's COVID-19 response was the increase in government welfare available to both businesses and individuals who had either lost revenue or their jobs due to the pandemic. The fortnightly coronavirus welfare supplements for individuals and businesses now supports approximately 2.25 million Australiansiii, iv, consequently offering much needed support to many struggling households and businesses whose income was negatively affected by the government lockdowns and restrictions.

The Learnings from Australia's COVID-19 Response

There have been many lessons learnt from Australia's response to COVID-19, namely the Occupational Health & Safety (OHS) coordination for many health care workers (HCWs), early failures in the quarantine processes and issues in contact tracing.

During the early stages of the pandemic, there were some major failures in quarantine procedures for different States that resulted in high rates of community transmission. In particular, there have been many instances, particularly in NSW and VIC, where there was a breakdown of communication between the State and Federal Governments and the different expectations and jurisdictions of each.

It also became quickly apparent in many workplaces that clinical areas were not suitable for maintaining the safety of staff, existing patients and allowing for the effective treatment of growing numbers of COVID-19 patients. There were many instances of poor ventilation, breakdowns in infection control, staff fatigue and community acquisition that led to high infection rates amongst HCWs that represented 9.1% of all Australian infections as of September 2020v. There have been many implemented changes due to this problem, with many clinical environments implementing measures such as upgrading PPE (N95 masks, face shields), closures of open wards, extra cleaning, rapid testing and services supporting infected and furloughed staff.

Another important lesson learnt during 2020 was the closure of respiratory laboratories and the advice needed. All non-essential tests were stopped at the end of March, with a resumption of services from the end of April, though still with restrictions in place for asymptomatic and afebrile patients. It was quickly uncovered that ventilation in laboratories was a major issue, as the age, size and ventilation of buildings all affected the safety of testing conditions. The number of laboratories situated in buildings without appropriate ventilation, air-conditioning, appropriately sized rooms and filters was problematic, and this, along with varied advice across different healthcare services and a lack of PPE, was concerning. Since July, there has been more coordinated advice from TSANZ and ANZSRS, however this has highlighted the need for structural modifications in many clinical buildings to help prevent the spread of the virus.

There are still many things we are learning about COVID-19 and there will be no straightforward path to help begin curbing global infection rates. However, from the Australian perspective, it has proven to be greatly beneficial to enforce a strong lock down early and quickly to stop the rapid spread of the virus. Furthermore, it is incredibly important to treat the infection of HCWs as a serious OHS issue as a means to look after their health and wellbeing as they help fight from the front line.

Further graphics for Australia from worldometers.info (PowerPoint file) submitted by Dr Philip Eng

Further graphics for New Zealand from worldometers.info (PowerPoint file) submitted by Dr Philip Eng

Taiwan

COVID-19 pandemic in Taiwan; what we have done and what we can do more

2 School of Medicine, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan

3 Institute of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, School of Medicine, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan

4 Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

5 President, Taiwan Society of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Taiwan

Reported cases and deaths of COVID-19 in Taiwan

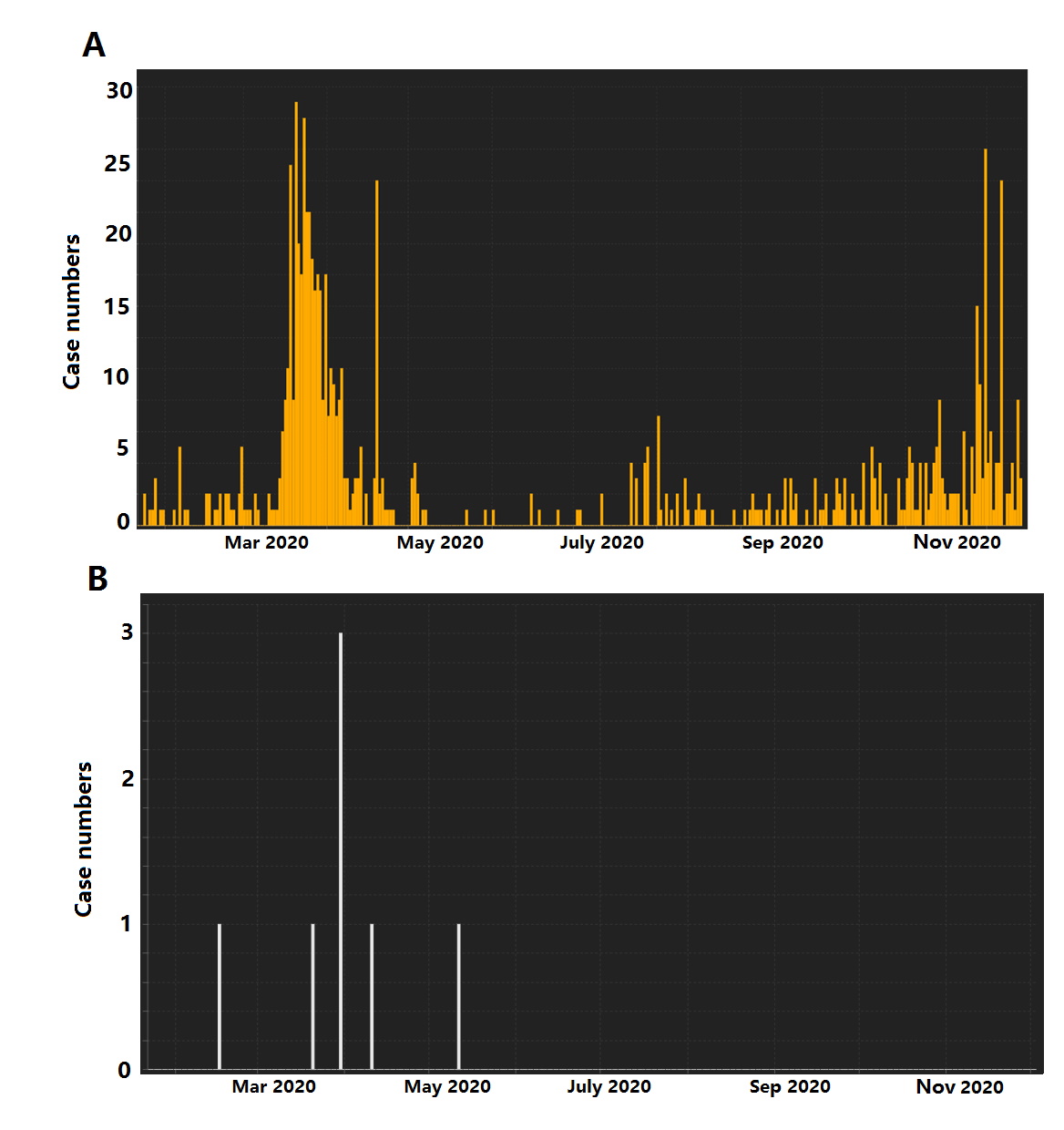

Since the first case of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) reported on 21 January in Taiwan (1), there have been 686 confirmed cases in Taiwan (as of 3 December). Among these patients, we have 7 deaths and 572 recoveries. As shown in Figure 1A, we can see two peaks of daily reported COVID-19 cases. The first peak occurred in March 2020 with maximum daily reported number of 27 cases. Most of these cases were imported cases of Taiwan citizens who returned from overseas (2). After April, the COVID-19 pandemic was under good control with daily reported cases below 10. The second peak has occurred since late November. Unlike the first peak, most of the reported cases in the second peak were foreign workers from Southeast Asian countries, rather than domestic people in Taiwan. As shown in Figure 1B, there are 7 reported deaths of COVID-19 cases in Taiwan, and there have been no more death cases after May 2020.

COVID-19 pandemics in Taiwan

Based on the experiences learned from SARS in 2003, Taiwan is very vigilant about new outbreaks (3, 4). Our medical care systems are well-prepared for upcoming pandemics (5). Since the first occurrence of COVID-19 at the end of December 2019 in Wuhan, China, our government issued several important regulations to prevent spread of COVID-19 from oversea countries (4). Our citizens are also alert to the highly contagious characteristics of SARS-CoV2 and have high adherence to face mask and travel ban to keep social distances. Our strategies against COVID-19 are successful. The daily reported new cases of COVID-19 are maintained at low level and the mortality rate of COVID-19 patient in Taiwan is only 1%. There is no community transmission of COVID-19 in Taiwan till now and our people can keep their regular daily activities as it was before COVID-19 pandemics. The schools are open and children maintain the regular learning progress. Our profession baseball games are not shut down and the stadiums are open to the public. Taiwan takes these credits because of the effective responses from our government and cooperation from the people in Taiwan.

What have been done in Taiwan

Some of the effective responses against COVID-19 pandemics in Taiwan are worth noting. The National Health Command Center (NHCC) was set up immediately after COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China, was confirmed in late January 2020. The daily press conference provided real time and accurate information to the community and had swift reaction to the pandemics. A series of border control regulations were issued by NHCC to impose entry ban on foreign visitors. NHCC also organized the industrial resources to maximize the production of personal protective equipment (PPE), face masks and rubbing alcohol to meet the domestic demand. They also used big data analytics to make sure the epidemic prevention materials and medical supplies, especially face masks, are evenly and effectively allocated to hospitals and the public (6, 7). In addition, vigorous contact tracing to assess COVID-19 transmission dynamics were carried out in each domestic reported COVID-19 case (8). The public is well-informed about the occurrence of COVID-19 pandemics and have good awareness of the importance to keep social distance. Our people have high adherence to wear face masks when taking public transportation and when staying in indoor spaces. The behaviour of our people is the key to keep Taiwan a country free of community transmission during COVID-19 pandemics. Finally, our medical care system is well-prepared for the upcoming outbreak after the SARS pandemics in 2003 (5). We have continuing medical education activities about infectious disease annually to keep our medical staff familiar with the epidemic preventive measures (9). Many hospitals have quick responses against outbreaks, even before the COVID-19 pandemics was announced by WHO (10). The negative pressure facilities are activated early to take care of confirmed COVID-19 cases. Strict measures are implemented inside hospital to prevent the occurrence of nosocomial transmission. We have sufficient inventory of epidemic preventive materials for medical personnel. So far, there is no report of COVID-19 cases in health care workers that results from taking care of COVID-19 patients (11).

What we can do more

Given the success in combating COVID-19 in Taiwan, we can actually do more. The medical resources in Taiwan are abundant and we can contribute more to the development of novel medication against COVID-19. Taiwan has good experience in performing medical studies and is willing to take part in clinical trials of anti-viral agents or vaccines against COVID-19. Meanwhile, our experiences in controlling COVID-19 are valuable to other countries that are suffering from COVID-19 pandemics. Crucial policies, including border control, community transmission prevention, bailout measures, and nosocomial infection control, are proven to be effective and valid in Taiwan. The world-wide spreading of COVID-19 has shown that SARS-CoV2 knows no borders. Taiwan cannot be a place free of COVID-19 unless COVID-19 is under good control in other areas. To jointly overcome the challenges from COVID-19, Taiwan can help and Taiwan is helping.

This article was submitted to the APSR Bulletin on behalf of the Taiwan Society of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine.

Further graphics for Taiwan from worldometers.info (PowerPoint file) submitted by Dr Philip Eng

Vietnam

Ngo Quy Chau, MD, PhD, and Vu Van Giap MD, PhD

Vietnam Respiratory Society

Epidemic curve

On 23 January 2020, Vietnam had its first two confirmed cases, a father and son from China, followed by a series of cases returning from Wuhan, China. Active monitoring, early detection of cases and suspects, and isolating, have brought good results. Up to 07:30 on 6 April 2020, Vietnam had only 241 confirmed cases and no deaths.

The 24 July 2020, after 99 days of no new COVID-19 cases from the community, marked the second phase of the COVID-19 epidemic in Da Nang, Vietnam. A series of COVID-19 cases was detected in hospitals and the city was locked down to control the epidemic. The measures of rapid contact tracing, isolation and strict control of points of entry, were effectively applied. Until the middle of September 2020, the COVID-19 epidemic in Da Nang and the central provinces was controlled, but this epidemic had a serious impact with nearly 400 cases, of which 35 died (all of them had underlining diseases such as end stage renal disease, diabetes mellitus or cancer). Currently, there are still imported cases, but no cases of community transmission. As of 19 January 2021, Vietnam had a total of 1,539 confirmed cases, of which 1,402 affected patients had recovered and discharged from hospitals. Vietnam has also recorded 35 deaths due to the pandemic.

For more information, please click this WHO webpage link covid19.who.int/region/wpro/country/vn

General comments about COVID-19 in Vietnam

Vietnam has a 1,400 km border with China, through which there is intense cross-border travel and trade with the population of over 97 million people. So the risk of COVID-19 transmission is very real. The Vietnamese Government promptly established a National steering committee for COVID-19 control with the motto of the Prime Minister: “fighting the epidemic as an enemy”. This commitment from the highest level of leadership was the key to the country’s success in containing the COVID-19 pandemic. Vietnam’s government made quick and effective responses against COVID-19, with unequivocal decision to prioritize health over economic growth. Vietnam was one of the first countries to halt passenger flights from high-risk areas and to quarantine international travellers. Since late January 2020, the government has required all people arriving from China (international airports, ports, ground crossings including small crossings through the long border) to submit a health declaration and undertake quarantine in government-controlled facilities for 14 days. These requirements were gradually expanded to those arriving from the Republic of Korea, the United States, EU, then all other countries. Vietnam has been mobilizing important resources and allocating them in the optimal way for the battle to counter the pandemic. The Government has utilized the media to give transparent information on the pandemic situation to the population. The Ministry of Health has rapidly issued updated guidelines for the management of COVID-19, provided guidance, manpower, equipment necessary to hospitals taking care of COVID-19 patients and organized telemedicine consultations with national specialists for severe cases.

Three things the country did well

- Points of entry have been tightly controlled, local authorities are taking a four-tier approach to contact tracing and isolation

- Epidemic control teams have carried out targeted testing and aggressive contact tracing

- Public compliance with precautionary measures: masking, social distancing, hand cleaning, etc

Three things the country could do better

- Tighten more rigorously the border and crack down on illegal immigration to limit imported cases

- Keeping more strickly the isolation regulation

- Vaccin Nanocovax against COVID-19 will be soon available.